I was sitting at a small, slightly overpriced coffee shop in the heart of South Jakarta the other day, just watching the usual traffic crawl by—a sight that, honestly, hasn’t changed all that much in the last decade—but I realized something felt fundamentally different. It wasn’t the speed of the traffic, because we all know the Jakarta “macet” is a constant of the universe. It was the sound. Or, to be more precise, it was the eerie lack of it. The aggressive, chest-rattling roar of those old two-stroke engines that used to define the city’s morning pulse has been steadily replaced by a high-pitched, almost futuristic whir. It’s a bit like living in a sci-fi movie that’s finally starting to feel like real life. We’ve finally hit that tipping point we all kept talking about back in 2022, and it’s fascinating to see it play out in real-time. According to the latest data from RISE by DailySocial, the Indonesian electric vehicle (EV) ecosystem has officially moved past the “early adopter” phase where it was just a hobby for the wealthy. We are now firmly entrenched in the messy, complicated, and incredibly exciting reality of mass-market integration.

It’s funny how we look back at the “Green Rush” of just a few years ago. Do you remember those days? Everyone was making these massive, sweeping promises, signing MoUs left and right like they were going out of style, and acting as if we’d all be silently gliding in Teslas across the Java-Bali toll road by lunch. But as we sit here in the early months of 2026, the reality is much more nuanced—and if I’m being honest, it’s much more interesting than the hype ever was. It’s not just about luxury cars for the elite anymore; it’s about the delivery guy swapping a battery in thirty seconds at a street corner and the middle-class family sitting around the dinner table realizing that their monthly fuel savings are actually enough to pay for their kids’ school fees. It’s a transition that’s happening in the bank accounts of ordinary people, not just in the glossy, air-conditioned brochures of high-end dealerships in North Jakarta.

But let’s be real for a second. This shift hasn’t been a straight line or some perfect success story. We’ve definitely had our fair share of “range anxiety” meltdowns and infrastructure hiccups that made us all question, at one point or another, if we were actually ready for this. We’ve seen chargers that didn’t work when it rained and software glitches that left people stranded. And yet, despite the bumps, here we are. The air in the city feels slightly cleaner—on some days, at least, when the wind blows the right way—and the local industry is finally finding its feet. We aren’t just passive consumers of this technology anymore; we’re becoming the literal heart of the global supply chain. That changes the entire geopolitical game for Southeast Asia, and it puts Indonesia in a position of power we haven’t seen in decades.

Digging for the Future: Why the World is Suddenly Obsessed with Indonesian Soil

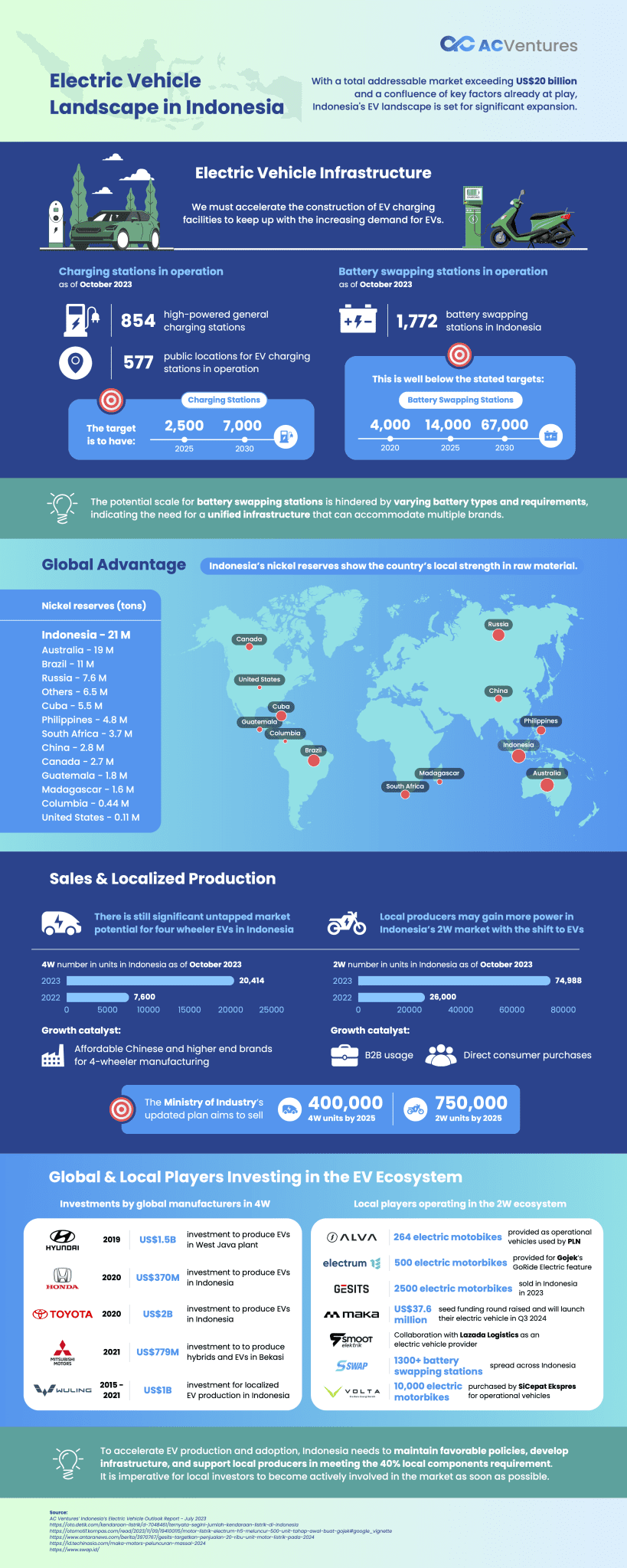

You really can’t have a serious conversation about EVs in Indonesia without talking about what’s buried deep under the ground in places like Sulawesi. For years, we’ve been hearing the government beat the drum about our massive nickel reserves, and by now, the downstreaming policy—which, let’s remember, was once considered a massive and controversial gamble—has largely paid off. According to Reuters, Indonesia’s nickel production accounted for nearly 50% of the total global supply by late 2024. That dominance hasn’t just held steady; it has solidified as we moved through 2025 and into early 2026. We aren’t just digging up raw dirt and shipping it off to be processed elsewhere anymore; we’re building the actual batteries that power the world’s transition to green energy. It’s a massive shift from being a raw material exporter to a high-tech manufacturing hub.

This “nickel diplomacy” has given Jakarta a seat at the big table that it simply didn’t have five years ago. When you control the single most expensive and critical component of an EV battery, people—and world leaders—tend to listen to what you have to say. But the editorial question we have to ask ourselves, and one that I think about often, is: at what cost? The environmental impact of mining in Sulawesi and Maluku is the massive elephant in the room that we’re only now finally starting to address with any real seriousness. It’s one thing to feel good about driving a “zero-emission” car in the city, but it’s another thing entirely if the process of making that car’s battery scarred a rainforest or polluted a coastline halfway across the country. The push for “Green Nickel” is the next big frontier for us, and it’s where the real credibility of our entire national transition lies. If we can’t mine it cleanly, the whole “green” argument starts to fall apart.

I think we’re finally seeing a shift in how the government and private sectors collaborate on this. It’s no longer just about extraction and profit at any cost; it’s starting to be about accountability. We’ve seen more ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) audits in the last eighteen months than I think we saw in the previous decade combined. Is the system perfect? Absolutely not. There’s still a lot of greenwashing to wade through. But the pressure coming from global investors and, perhaps more importantly, the younger generation of Indonesians who actually care about the planet, is making it impossible for companies to ignore the “dirty” side of clean energy. We’re learning the hard way that a truly sustainable ecosystem requires a transparent supply chain, not just a flashy, silent product at the end of the assembly line.

“The transition to electric mobility isn’t just a technological swap; it’s a fundamental restructuring of how a nation moves, breathes, and powers its future.”

— Senior Energy Analyst at the 2025 ASEAN Decarbonization Summit

Plugging In: How We Finally Solved the Chicken-and-Egg Infrastructure Problem

If 2024 was the year of the “New Car Launch” where every month seemed to bring a new model, then 2025 was definitely the year of the “Charging Station.” We finally seem to have moved past that frustrating chicken-and-egg problem that stalled the market for years. For a long time, people wouldn’t buy EVs because there were no chargers, and companies wouldn’t build chargers because there weren’t enough EVs on the road to make it profitable. It was a stalemate. But a 2025 Statista survey showed a fascinating trend: over 60% of Indonesian urbanites now prioritize charging availability over vehicle range when they’re looking to buy. That’s a massive psychological shift. People are realizing that they don’t need a 1,000km range if they can top up their battery as easily as they can grab a coffee.

The rise of battery-swapping technology for two-wheelers has been the real, unsung hero of this story. While the rest of the world seemed obsessed with high-speed superchargers for expensive cars, Indonesia realized that its true lifeblood is the motorbike. Companies like Grab and GoTo have basically forced this infrastructure into existence through sheer scale. It’s a fascinating example of how local problems require local solutions. We didn’t wait for some “Western” model of EV adoption to be handed down to us; we built one that actually fits the beautiful chaos and high density of cities like Jakarta and Surabaya. You see these swapping stations everywhere now—at convenience stores, at malls, even in residential alleys. It just works for the way we live.

And let’s talk about the grid for a moment, because that was another big fear. There was so much anxiety that the PLN (State Electricity Company) wouldn’t be able to handle the massive new load. But the integration of “smart charging”—where cars are incentivized to charge during off-peak hours at much lower rates—has actually helped balance the grid in ways we didn’t quite expect. It turns out that having millions of “batteries on wheels” can actually be a massive asset for a national power grid, acting as a buffer, rather than just being a drain on resources. We’re even seeing the first real experiments with vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology in some of the newer gated communities in BSD City. If that can scale, it could fundamentally change how we think about household energy and backup power forever. Imagine your car powering your house during a blackout—that’s the direction we’re heading.

The 400 Million Rupiah Question: Is an EV Actually for Everyone?

Despite all the progress we’ve made, we have to talk about the “sticker shock” that still exists. Even with the various subsidies that were rolled out last year, a decent electric car still feels like an unattainable luxury for many people. The “middle-class trap” is a very real thing in Indonesia. If you’re earning a solid salary but you still have to worry about a mortgage, rising food prices, and school fees, dropping 400 million Rupiah on a new car—even if the running costs are incredibly low—is a really tough pill to swallow. This is where the secondary market and more innovative financing models really need to step up. We need more than just subsidies; we need a way for the average family to see a clear path to ownership.

I’ve noticed a lot of my friends aren’t even looking at new cars; they’re opting for “conversions” instead. They’re taking their old, reliable petrol bikes that have been in the family for years and swapping the internal guts for an electric motor. It’s a brilliant solution, really. It’s cheaper, it’s arguably more sustainable than manufacturing a whole new machine from scratch, and it keeps the old chassis out of the landfill. This “grassroots” EV movement is something the big global manufacturers didn’t really see coming. It’s a very Indonesian way of doing things—fixing and upgrading what you already have instead of always reaching for the newest, shiny object on the showroom floor. It shows a level of ingenuity that I think defines our market.

A 2024 McKinsey report noted that Southeast Asia’s EV market could reach a staggering $20 billion by 2030, but that growth is heavily dependent on hitting that sweet spot: the sub-$20,000 price point. We’re currently seeing more Chinese and Korean manufacturers flooding the market with these “affordable” models, and it’s putting massive, unprecedented pressure on the traditional Japanese giants who were, let’s be honest, a bit slow to the party. The competition is fierce right now, and the winner is going to be whoever can figure out how to make a car that can survive a Jakarta flood while costing less than a year’s worth of fancy lattes. It’s a tall order, but the brands that get it right will dominate the next decade of Indonesian transport.

Is the Government Doing Enough, or Just the Bare Minimum?

The policy landscape has been a bit of a rollercoaster, hasn’t it? We’ve had the “carrots”—tax breaks, free parking in certain areas, and even those coveted exemptions from the “odd-even” traffic rules that make life so much easier. These are great incentives, but we’re starting to see the “sticks” arrive too. There’s more and more talk in the halls of power about higher taxes on older, high-emission vehicles and creating more restricted low-emission zones in city centers. It’s a classic move: make the old way of doing things increasingly painful while making the new way look more and more attractive. It’s a push-and-pull strategy that’s starting to yield results, even if it feels a bit forced at times.

But the real test, the one that keeps me up, is the “Just Energy Transition.” We absolutely cannot afford to leave the rural areas behind. It’s easy to own and charge an EV in a place like Jakarta or Tangerang, but what about someone living in rural Kalimantan or on a small island in NTT? The infrastructure gap between the cities and the rest of the country is still incredibly wide. If the EV revolution stays a “big city” phenomenon for the urban elite, then we’ve failed the mission. We need to see more investment in off-grid solar charging for remote areas to ensure that the benefits of cleaner, cheaper transport are shared by everyone, regardless of their zip code. Equity has to be part of the equation, or the transition won’t be sustainable in the long run.

Is it really cheaper to own an EV in Indonesia now?

Yes, absolutely—but you have to look at the long game. In terms of daily running costs, there’s no contest. With current electricity rates compared to the subsidized fuel prices we’re seeing in 2026, an EV user typically spends about 70-80% less on “fuel” per kilometer. However, you have to factor in that initial purchase price, which is still significantly higher than internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. For the average driver, it takes about 3 to 5 years to reach a “break-even” point where the savings have covered the extra cost of the car. If you drive a lot, like a ride-sharing driver, that break-even point comes much faster.

Can I actually take an electric car on a long road trip across Java?

You can, and it’s actually become quite a common thing to do. As of early 2026, the Trans-Java toll road has fast-charging stations at almost every major rest area along the route. While you still need to do a bit of planning and maybe check an app before you head out, the days of being genuinely terrified of being stranded with a dead battery in the middle of Central Java are mostly over. Most new EVs on the market now have a real-world range of 350-400km, which is more than enough to cover the stretches between the major cities. It just requires a slightly different mindset than a petrol car.

Looking Toward 2027: The Road Ahead and Why I’m Optimistic

So, where exactly does this leave us? I think we’re currently in what I call the “boring” part of the revolution, and honestly, that’s actually a very good thing. The initial novelty has worn off, the hype has settled down, and the actual utility has set in. EVs are no longer a status symbol for the tech-obsessed or a weird experiment for the brave; they’re just… cars. And bikes. And buses. The TransJakarta fleet is now almost 40% electric, and if you’ve ridden one of the new ones lately, you know how much better the experience is. It’s quiet, there’s no vibration, and you don’t step off the bus smelling like diesel fumes. It’s a small improvement that makes a huge difference in the quality of daily life.

The next two years are going to be all about refining what we call the “circular economy.” It’s the big question: what do we do with all these batteries when they eventually degrade and can no longer power a car? We’re already seeing the first dedicated battery recycling plants breaking ground in places like Morowali. If we can successfully close that loop and recycle the materials back into the system, Indonesia won’t just be a leader in EV production; we’ll be a global blueprint for how a developing nation can leapfrog traditional, dirty industrialization and go straight to a truly sustainable model. That’s a legacy worth building.

And honestly, that’s the most exciting part of this whole journey. It’s not really about the cars themselves, at least not for me. It’s about the sheer audacity of the shift we’re attempting. We’re watching a nation of 280 million people rewire its entire relationship with energy and movement in real-time. It’s messy, it’s expensive, and it’s occasionally incredibly frustrating—but standing on that street corner in Jakarta, listening to the quiet, steady hum of the future passing by, it’s hard not to feel a sense of optimism. We’ve traded the loud, smoky roar of the past for the quiet whisper of what’s next, and I think we’re finally ready for the ride. Let’s see where the road takes us.

This article is sourced from various news outlets and industry reports. Analysis and presentation represent our editorial perspective on the evolving landscape of Indonesian mobility.