It’s hard to believe it has already been a full year since Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore finally felt the pull of Earth’s gravity again. Their “short trip” to the stars—a mission that was supposed to be a quick week-long victory lap for Boeing—somehow spiraled into an eight-month residency on the International Space Station. We all remember watching that saga play out in the headlines through late 2024 and into the early months of 2025. There was this collective breath-holding, a constant, nagging question: would Boeing’s troubled capsule ever actually be trusted with human lives again? Well, the wait for an official answer is over. According to recent reports from CNET, NASA has finally stopped the polite corporate speak and started calling things by their real names. They’ve officially slapped the Starliner mission with a “Type A” mishap label. In the aerospace world, that’s essentially the equivalent of putting a “Totaled” sticker on a car’s windshield—only this car cost billions of dollars and was supposed to be the shining future of American spaceflight.

If you were to walk through the halls of NASA today, the atmosphere is noticeably different than it was just two short years ago. There’s a palpable sense of accountability in the air, and frankly, it feels a bit overdue. By classifying this as a Type A mishap, the agency is essentially making a public confession. They are admitting that the mission either resulted in a total direct cost of failure exceeding $2 million (and let’s be real, the actual figure is closer to $4.2 billion) or involved the loss of a crewed aircraft hull. Since the Starliner eventually limped back to Earth empty while its intended passengers had to wait for a SpaceX “Uber” to get home, the mission hits both of those criteria squarely on the head. It’s a heavy, somber label, but it’s the honest one. And honestly? We needed that level of transparency a long time ago. The public deserves to know exactly where the line was crossed between “technical glitch” and “systemic failure.”

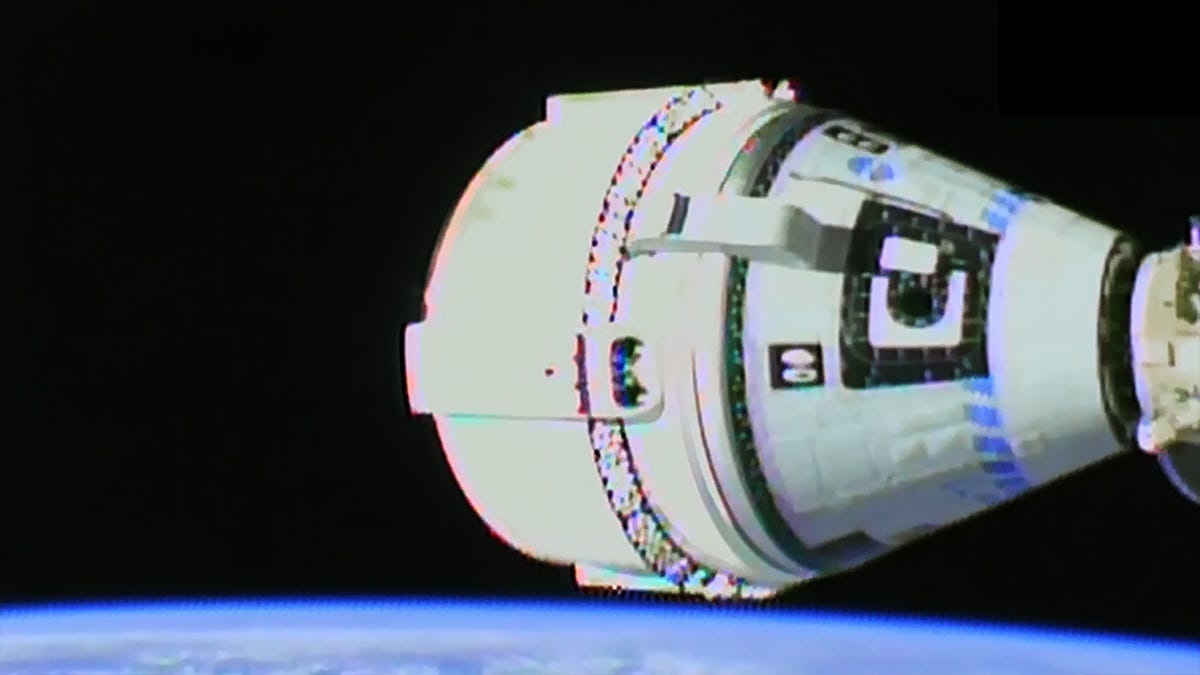

“While Boeing built Starliner, NASA accepted it and launched two astronauts into space. The technical difficulties encountered during docking with the International Space Station were very apparent.”

Jared Isaacman, NASA Administrator

Why Are We Paying a $2 Billion Premium for a “Maybe”?

Let’s take a minute to talk about the money, because $4.2 billion is one of those numbers that is so massive it starts to feel abstract, like something out of a sci-fi novel. But it’s very real. To put that in some much-needed perspective, a 2020 report from the NASA Office of Inspector General highlighted that SpaceX developed its Crew Dragon capsule for roughly $2.6 billion. That means we are looking at a nearly $2 billion premium for a spacecraft that, as of February 2026, still hasn’t managed to pull off a seamless, hitch-free crewed mission. It really makes you stop and wonder where the disconnect happened. Was this a classic case of a company being “too big to fail,” or did we as a nation just get a little too comfortable with the “old way” of doing things—the slow, expensive, bureaucratic way? It’s a bitter pill to swallow when you realize that the more expensive option has, so far, been the less reliable one.

The “Type A” designation isn’t just another boring bureaucratic checkbox for the archives; it’s a flare being shot into the sky. It’s a signal that the internal investigation is finally getting serious. NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman hasn’t been pulling any punches lately, which is a refreshing change of pace. In his recent notes on X and various blog posts, he’s been surprisingly blunt, pointing out that there were significant risks with the thrusters that were “never fully understood” before the launch back in June 2024. Think about that for a second. That is a genuinely terrifying sentence to read when you realize there were human beings sitting on top of those thrusters, hurtling through the atmosphere. It suggests a culture where “good enough” was allowed to override “absolute certainty.” In the vacuum of space, that kind of compromise is a recipe for the exact kind of nightmare headlines we saw dominating the news cycle all through last year.

But there is a silver lining here, if you’re looking for one. NASA is finally stepping up and taking its fair share of the blame. For the longest time, the narrative was very one-sided: “Boeing messed up.” It was easy to point the finger at the contractor. But now, Isaacman is making it crystal clear: NASA signed the paperwork. NASA looked at the data and said it was a go. That kind of radical transparency is probably the only path forward if they want to rebuild public trust. We need to know that the people in charge aren’t just passing the buck. As we look toward the uncrewed resupply mission currently slated for April 2026, this honesty is vital. If they’re going to fix the ship, they first had to have the guts to admit it was broken in the first place.

The Long Shadow of the “Stranded” Narrative

It’s still hard to shake that image from late 2024—the one of Suni and Butch waving goodbye to an empty Starliner as it undocked from the ISS. They were left behind, watching their ride home leave without them because it wasn’t safe enough to carry them. They didn’t actually set foot back on Earth until March 2025, which was nearly a year ago today. While they handled the entire ordeal with the incredible grace and professionalism you’d expect from seasoned pros, the delay in officially declaring the mission a failure was palpable. Everyone on the ground knew it, the journalists covering the beat knew it, and I’d bet my house that the engineers knew it, too. Yet, the official declaration of a “mishap” took until right now. It felt like we were all watching a movie where the ending was obvious, but the credits refused to roll.

So, why the long wait? Why did it take until February 2026 to call it what it was? Part of it is undoubtedly legal and contractual. When you’re dealing with a corporate behemoth like Boeing, every single word in a public statement is litigated, scrubbed, and analyzed by teams of lawyers. But another part of it is the sheer psychological weight of that “Type A” tag. Once you use those words, it triggers massive internal audits, intense oversight, and a level of scrutiny that most projects want to avoid at all costs. According to data from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), major NASA projects often see a 20% to 30% cost growth when technical baselines aren’t met early on. Starliner hasn’t just met those averages; it has blown past them. By officially calling it a mishap, NASA is essentially forcing a hard reset on the entire Boeing partnership. They’re saying the old rules don’t apply anymore.

I remember catching up with a friend of mine who works in aerospace engineering right after the Crew-9 mission finally brought the duo home last year. He told me something that stuck with me: the most frustrating part for the guys in the trenches wasn’t the thruster failure itself. Hardware fails. It’s space; it’s hard. The real issue was the “disagreement among leadership” that Isaacman recently admitted to. There was a genuine rift behind closed doors—a battle between the faction that wanted to risk the return on Starliner to save face and the faction that said “absolutely not.” Thankfully, the cautious voices won out. If they hadn’t, we might be having a much darker, much more tragic conversation today than one about budget overruns and missed deadlines. We came closer to a catastrophe than many people realize.

Deciphering the “Root Cause” in a 2026 World

Here’s the real kicker: we’re sitting here in February 2026, and they still haven’t identified the “true technical root cause” of why those thrusters decided to give up the ghost. Isaacman says they’re getting “close” and that they aren’t “starting from zero,” but let’s be honest—it’s been nearly two years since that launch. If you’ve ever had a car that made a weird, intermittent clicking noise that the mechanic could never quite find, you know that feeling of low-level anxiety every time you turn the key. Now, imagine that “car” is traveling at 17,500 miles per hour in a total vacuum, and your life depends on it. That’s the level of uncertainty we’re dealing with here, and it’s not exactly a confidence booster.

The investigation has recently pivoted back toward the “OFT thruster risk” that was apparently flagged but largely ignored in previous years. This refers to the Orbital Flight Test issues that cropped up way back when. It turns out the ghosts of missions past were still haunting the hardware. It’s a classic, textbook case of “normalization of deviance”—a term that became tragically famous after the Challenger disaster. It’s what happens when you see a small problem, it doesn’t kill anyone, and so you start to convince yourself that the problem isn’t actually a problem. You get used to the flaw. Until, one day, the flaw decides it’s done being ignored. It’s a dangerous psychological trap, and it seems Boeing fell right into it.

Now, NASA and Boeing are locked in a frantic, high-stakes race to get everything right for the April 2026 uncrewed resupply flight. This isn’t just another mission; this is Starliner’s last chance at redemption. If it can’t deliver cargo safely to the ISS, there is absolutely no way it’s getting another pair of boots inside. The agency has committed to making it “launch-worthy” again, but the clock is ticking louder than ever. We’re witnessing a massive, fundamental shift in how NASA handles these private-public partnerships. The “hands-off” approach that seemed to work so well in the early days of the Commercial Crew Program is being scrapped. In its place is a much more rigorous, almost suspicious level of oversight. The honeymoon phase is officially over.

What exactly is a Type A mishap?

In the world of NASA bureaucracy, a Type A mishap is the highest level of accident classification. It’s triggered when a mission results in property damage of $2 million or more, the total loss of a crewed aircraft, or—heaven forbid—a permanent disability or fatality. In the case of Starliner, the massive financial loss and the fact that the ship was deemed unsafe to return its crew as planned were the primary triggers for this status. It’s essentially the agency admitting the mission was a failure.

When did Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore return to Earth?

After launching in June 2024 for what was originally billed as a quick eight-day stay, the duo ended up living on the ISS for a staggering eight months. They finally made it home safely in March 2025, but not on the ship they arrived in. They had to hitch a ride on a SpaceX Crew Dragon as part of the Crew-9 mission, leaving the Starliner to return to Earth autonomously and empty.

What’s Next for the Starliner Program?

So, where do we go from here? The Starliner story is far from over, but the ending is definitely still being written in pencil. The upcoming April 2026 launch is going to be, without a doubt, the most scrutinized resupply mission in the history of the International Space Station. There is an incredible amount on the line—not just for Boeing’s reputation, but for the very idea of having multiple American companies capable of reaching orbit. We don’t want a monopoly in space, even if SpaceX is doing a fantastic job. We need redundancy. We need a backup plan. But we certainly don’t need redundancy at the cost of human safety. The price of a backup shouldn’t be a gamble with people’s lives.

Looking at the bigger picture, this entire ordeal has fundamentally changed the way we view the “New Space” era. It turns out that even the old guard—the giants who built the rockets that took us to the moon—has to learn new tricks if they want to keep up in this fast-paced environment. The fact that NASA is planning to share the results of multiple investigations in the coming days is a really good sign. It means they’re done hiding behind the shield of “proprietary information” and are moving toward a more open-source safety culture. That’s the kind of culture that makes commercial aviation so safe today. According to a 2023 Statista report, the global space economy is projected to reach a staggering $1 trillion by 2040, but that growth depends entirely on the reliability of the “buses” taking us there. If we can’t trust the ride, we aren’t going anywhere.

I’m trying to stay cautiously optimistic. I truly want to see Starliner succeed, because I want to see us have a robust, multi-faceted presence in Low Earth Orbit. But more than that, I want to see a NASA that isn’t afraid to call a spade a spade. Admitting fault is the first, most difficult step toward actually fixing the problem. It took a long time to get to this “Type A” admission, but now that we’re here, maybe we can finally put the ghosts of 2024 to rest. Maybe we can get back to the actual business of exploring the stars without the “stranded” headlines and the billion-dollar apologies. It’s time to move forward, but only if we’ve actually learned the lessons of the past.

This article is sourced from various news outlets. Analysis and presentation represent our editorial perspective.